This article was originally published on WordPress in September 2019. Revisions have been made to provide additional context and information on the subject.

When we talk about horror film history, it’s inevitable to single out certain years that mark significant milestones for the genre. The year 1968, for example, gave us Night of the Living Dead, that indie classic which forever redefined the word “zombie” without even uttering it. 1978 cemented the zombie’s place in the horror pantheon with Dawn of the Dead, while Halloween gave us the first mainstream slasher villain in Michael Myers. 1979 sent horror into the far reaches of space with Alien. 1981 can’t be overlooked with its groundbreaking double feature of The Howling and An American Werewolf in London (and we mustn’t forget The Evil Dead, either). 1987 made vampires cool again with The Lost Boys and Near Dark.

But these all pale in comparison to the importance of the year 1931. Perhaps - no, definitely the most crucial year ever for horror films. Because that was the year Universal released two of the greatest and most influential horror films of all time: Dracula and Frankenstein.

Because Dracula came out first, premiering in February of that year, we will first turn out attention to that film. Or rather, films, because there are actually two versions of this chilling cinematic achievement. That’s right, we’re going to talk about the original English version and the Spanish-language remake, considered by some critics to be superior to its counterpart. Is it truly the better film? For now, let me assure you that both versions are scary good - with emphasis on the scary.

The Plot: A ship full of corpses washes ashore on the coast of England, shocking those who first find it. The only survivor of this grisly, inexplicable tragedy is a man called Mr. Renfield (Dwight Frye in the English film, Pablo Alvarez Rubio in the Spanish film). An English lawyer, Renfield went off to Transylvania on business as a perfectly ordinary fellow but returns now as a cackling madman. He is placed under the care of the elderly Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston/Jose Soriano Viosca) at a sanitarium, where the origin of his madness remains a mystery. But Renfield’s talk about consuming lives and following the orders of his unseen master takes on new meaning when Count Dracula (Bela Lugosi/Carlos Villarias), an urbane Transylvanian aristocrat, moves into the ruined estate next door. Soon women all over London are dying of a strange malady, and it looks like Seward’s daughter Mina (Helen Chandler/Lupita Tovar) will become the next victim. Seward calls on the help of his friend Professor Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan/Eduardo Arozamena), who deduces the terrible truth: Dracula is a vampire, and he’s turning Mina into one as well. Can our heroes stop him before he claims another innocent soul?

Part 1: English Dracula

To begin, I must give you some background information. The year is 1924. Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker’s widow, is in the middle of a legal dispute with Prana Film, the German studio that made the unauthorized Dracula adaptation Nosferatu. In order to recoup the costs of this dispute, she allowed the playwright and actor Hamilton Deane to write and produce an official stage adaptation of the novel. Deane gets right to work, and the play premieres in August of that year. The production then tours England until February 1927, when it takes up residency in London. The play is popular enough to get the attention of American producer Horace Liveright, who plans to open a Broadway production. For whatever reason, the original Deane script is not used for this. Instead, Liveright hires John L. Balderston to revise the script for American audiences. This version of the play premieres in October 1927 and runs for 261 performances.

The Deane script condenses the novel’s plot and adds an additional female part but is still a fairly close adaptation. The Balderston script is…not. It cuts the first two acts of the novel, gets rid of several characters, combines the two female leads into one role and turns her into a helpless damsel. You will not like it if you’re a Dracula purist. But the play was a critical and financial success, and it was easier to produce than a full adaptation of the novel would have been. So when Universal acquired the film rights to Dracula, screenwriter Garrett Fort based his script on the Broadway production (Deane and Balderston are both credited in the final film). Three of the actors from the Broadway production even found their way into the film cast - we’ll meet them later.

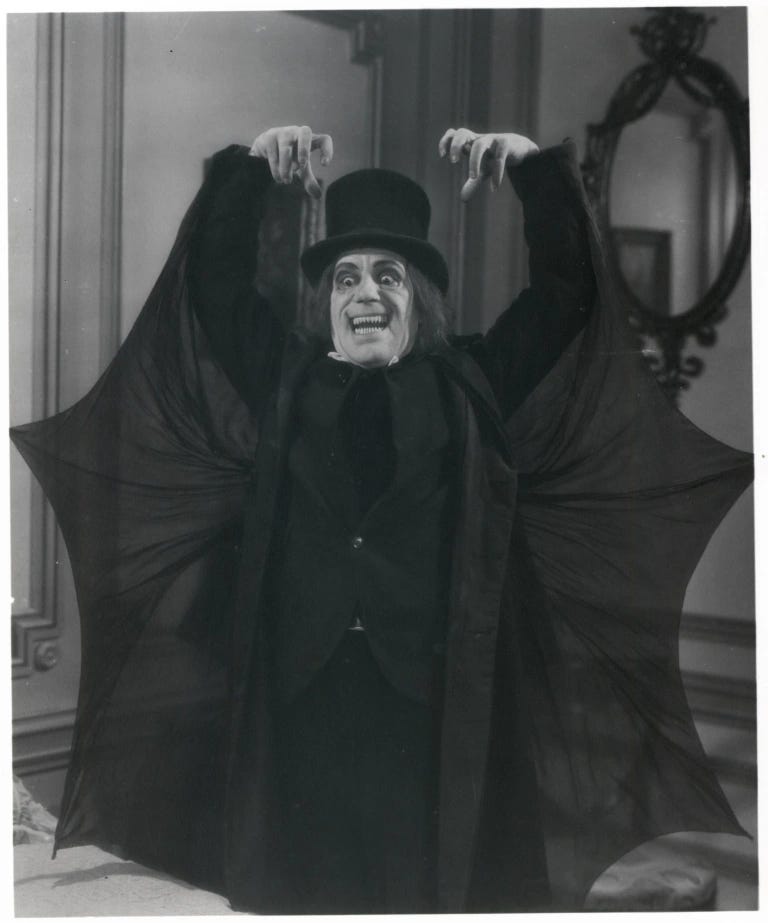

To direct the project, producer Carl Laemmle Jr. (son of the original Carl Laemmle) hired Charles Albert Browning Jr., better known by his professional name Tod Browning. Browning had a rather colorful history: before becoming a filmmaker, he had literally run away from home to join the circus, working as a clown, a contortionist and a sideshow barker. He even developed a special act in which he played the “Living Hypnotic Corpse” and was buried alive in a ventilated coffin (Herzogenrath 10). Drawing from these experiences, his films were often strange and provocative with a macabre flair. He was called the Edgar Allan Poe of cinema, and his closest modern equivalents would be directors like David Lynch, David Cronenberg and Alejandro Jodorowsky (Herzogenrath 17). Basically, he made weird stuff. His most famous film besides Dracula was 1932’s Freaks, which at the time of its release was extremely controversial for casting real sideshow performers and for sequences of graphic violence that were censored and subsequently lost. In 1927, he made a now-lost vampire film called London After Midnight, in which Lon Chaney ran around looking like this:

It should be noted that Browning was said to have become disinterested in Dracula during production, leaving much of the actual directing work to his cinematographer Karl Freund. Remember that name, because we’re going to see him again in the future. However, Browning’s contributions to the film should not be minimized: his personal background and cinematic passions both help make Dracula as creepy as it is.

Like the script itself, the film’s cast mostly came from a theater background. Dwight Frye had found some success as a stage actor, but he had only done a few minor film roles before playing Renfield. Helen Chandler had been acting on Broadway since she was ten years old, and before doing Dracula, she had played the female lead in Outward Bound opposite Leslie Howard (of The Scarlet Pimpernel and Gone With the Wind fame) and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. David Manners, who plays Mina’s fiance John Harker, was also an up-and-coming actor at the time. I mentioned earlier that three actors from the Broadway production of Dracula were also cast in the film. Two were Edward Van Sloan and Herbert Bunston who reprised their roles as Van Helsing and Seward. The third is a man who needs no introduction, but I shall give him one anyway. A horror icon of his magnitude deserves nothing less.

Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó was born in 1882 in Lugos, Hungary (now part of Romania). He began acting onstage in the early 1900s, served in World War One and eventually fled Hungary following the revolution of 1919. By this point he had adopted the stage name Bela Lugosi, the surname being a reference to his hometown. Lugosi came to America in the early 1920s, settled in New York and started acting in Hungarian-language plays with fellow expatriates. He soon took up English-language roles, learning his lines phonetically. Rather than hampering his acting ability, this gave him a “certain unclassifyable [sic] distinction” (Mallory 60) that set him apart from his contemporaries. While Lugosi did eventually learn English, he always retained his thick Hungarian accent. That accent and his peculiar English cadence made him an ideal actor to play the strange, foreign Count Dracula. Not only did he originate the role on Broadway, but he was part of a West Coast touring production as well. Despite this cred, he had to lobby hard for the chance to play Dracula on film: Universal wanted a more bankable actor like Lon Chaney or Conrad Veidt. Lugosi would finally win the role by agreeing to a paltry salary of $500 per week, amounting to $3500 total (Lennig 137).

With decades’ worth of parodies and family-friendly takes on Dracula, most of them specifically referencing Lugosi, you may be tricked into thinking the original film can’t be all that scary. But in its own special way, it very much is. There’s an unrelenting eeriness about Dracula that grabs hold of you from the beginning and never lets go. A lot of that is due to Lugosi’s performance, but it also comes from the bleak, lonely nature of the rest of the film.

The first thing you’ll notice about Dracula is that it feels like a silent film lost in the talkie era. Outside of playing a Swan Lake snippet over the opening titles and having diegetic background music when the characters are at a symphony, there is no soundtrack. There isn’t much in the way of sound effects, either, which means that a good chunk of the film plays out in dead silence. Sure, there’s plenty of dialogue, but when there isn’t? It’s quiet, and you feel that. Modern home media releases of Dracula usually come with the option to play the film with a 1999 score by Philip Glass, but I’m reviewing the original version since that’s what audiences in 1931 would have experienced. The lack of music and sound makes the atmosphere of the movie pretty grim. There’s tension in the silence: you know something has to break it eventually, but you don’t know what or when. And when the break in the silence does come, through a scream or a deranged laugh or even just a line of dialogue, it catches you off-guard.

Another element that enhances the dark nature of the film is just how well it depicts vampirism as a sorry state of existence. Everything from the set design to the makeup to the costumes really plays up the undead aspect of these monsters. They’re pale and haggard, and their preferred haunts are crumbling castles and dusty tombs. Dracula is the only one who actually talks: the three Brides just stagger around in grim silence, emphasizing their fundamental nature as moving corpses. Every move the vampires make is slow and deliberate, like even the basic act of walking doesn’t come naturally to them. Everything about their demeanor feels off. Even the vampires themselves seem to know on some level that they aren’t supposed to be alive. As Drac himself says, “To die, to be really dead, that must be glorious…there are far worse things awaiting man than death.”

Like Phantom before it, Dracula is a movie that works as well as it does because of some excellent lead performances. Lugosi is at the center of that, with his Dracula still being the standard by which all others are judged. Believe it or not, Lugosi’s Dracula and that crazy-looking dude from London After Midnight have more in common than you might think. You see, neither of them care much about trying to appear normal. They live in the uncanny valley where something is not quite a monster but definitely not human, and that’s where the fear they induce comes from. Lugosi, I think, brings an elegance and determination to the character that would have been lost with a different actor. His Dracula is a subtle figure, able to act urbane and gentlemanly when the situation calls for it. But with him, there’s always a sense of tension and menace bubbling beneath the surface. When he isn’t being watched, or when things aren’t working out in his favor, that tension manifests as steely intimidation that is chilling to witness. Some of the film’s best moments happen when he drops all pretense of being the nice guy; the standout example is when Dracula tries to attack Van Helsing, first through intimidation and then through mind control that Van Helsing barely resists. It’s a wonderfully tense confrontation that plays out not as a big fight, but as a battle of wits and wills between two old masters.

But Lugosi isn’t the only great part of this movie. Here’s a big secret: Dracula has not only one of the best Draculas out there, but also one of the best — if not the best ever — version of Renfield.

In Bram Stoker’s book, Renfield is not a terribly important character. He spends most of his time off to the side acting creepy, and then Dracula kills him once he’s no longer useful. He only gets a little bit of sympathy before he dies. The stage adaptation gave this character an expanded role, which the film script then expanded even further. Renfield replaces Jonathan Harker as the character who goes to Transylvania and ends up as Dracula’s prisoner while helping him get to England, with the added bonus of Dracula doing…something to him that drives him insane. It’s supposed to be a bite, but we never see exactly what happens, which makes it all the more creepy. But the main change to Renfield’s character is how the narrative treats him. He goes from being a cackling minion to a tragic anti-villain. He’s aware on some level that he’s being destroyed and controlled by this malevolent force, and he has moments of lucidity where he’s clearly trying to seek help and prevent more people from getting hurt. But no matter how hard he tries, he can’t dig himself out of the hole he’s been dragged into. The sympathy you feel for him is definitely increased by Dwight Frye’s performance, which doesn’t really get talked about these days but is easily on par with Lugosi’s work. The way he flips back and forth between wide-eyed menace and desperate helplessness, sometimes in the same scene or shot, is seamless and incredible to watch. You can hear the change in his voice and see it in the way he holds himself. The writing and the acting combined bring a lot of humanity to this character that wasn’t fully realized in the book and is absent from most other adaptations. It feels a bit odd to phrase it this way, but if Dracula himself is the crown jewel of this film, then Renfield is its heart. He is Dracula’s first victim, and the one who ultimately suffers the most. This is, in my mind, the quintessential version of the character and one that no subsequent adaptation has come close to matching.

The movie’s not perfect, of course. There are the things most people make jokes about, like how armadillos and opossums are used as a stand-in for rats inside Dracula’s castle, plus the random bee with its own tiny coffin. But my main issue with the film is all the threads it leaves hanging. Lucy’s plotline is cut down to only a handful of scenes: she gets attacked by Dracula once, promptly dies and returns as a vampire sometime later. But for whatever reason, the scene of the heroes killing her is cut from the story. It’s not that we simply don’t see it, it’s never even alluded to. Nor is it a situation where the heroes never find out what happened to Lucy, because they do. It’s just odd that we don’t even get a quick line of dialogue to provide closure for that part of the plot. The ending is also fairly abrupt as well: Dracula dies offscreen, Jonathan and Mina are reunited and ascend from the vampire’s ruined hideout into the light of day while Van Helsing makes a comment about some unfinished business inside the tomb. What exactly that is, we never find out (at least in the English version). So the ending is less of a quick incline and more of a sudden, jarring stop. Film scholars like Uli Jung and Elisabeth Bronfen have interpreted the ending as a way to deny the audience a true resolution, a hint that Dracula - or at least the evil that created and drove him - is not so easily defeated (Bronfen 157-158). The film was originally supposed to end with a fourth-wall-breaking epilogue taken from the original play, in which Van Helsing’s actor appears to tell the audience that if all this talk of vampires frightens them, they should remember that “there are such things” (Bronfen 161). The ending of the final film, while a victory for the heroes, is still tinged with the same gloominess that pervades the rest of the story.

If you’re a fan of horror and vampires, Dracula is obviously required viewing. If you’re looking for a close adaptation of the original novel, you’ll most likely find it lacking. But that doesn’t make it a poor adaptation by any means. Instead, Browning and Freund do an incredible job of translating the book’s creepiness to film. The opening sections in Transylvania are a triumph of Gothic visual design, especially when Renfield gets to the castle. The slow-paced dialogue and moody cinematography give the whole film an unsettling, nightmarish feel. Bela Lugosi and Dwight Frye are at the top of their game, crafting definitive versions of Dracula and Renfield. True, a few of the supporting performances are average, and some moments in the script are lacking. But in the end, we don’t really remember the flaws in Dracula. They’re outshone by the moments of brilliance which have rightfully stood the test of time and remain part of our cultural subconscious to this day.

Final Rating: 4 Stars

Part 2: Spanish Dracula

So, what exactly is this movie? I called it a remake in the introduction, but that’s simplifying the situation somewhat.

Back in 1931, talkies were just starting to become commonplace. The technology for dubbing and subtitles didn’t exist yet. So in order to present an English-language movie to a non-English-speaking market, studios would essentially make the movie again in the new language. It wasn’t quite the same thing as the foreign remakes we get nowadays, because the goal was to replicate the original product. The Spanish-language Dracula, for example, was filmed on the same sets as the main production and used almost the exact same script.

The films that usually got this kind of treatment involved known stars like Laurel & Hardy or Buster Keaton, who would learn their lines phonetically. But Dracula didn’t fit that criteria, so why was it chosen? Allegedly, the production came about because Universal producer Paul Kohner was in love with Lupita Tovar, a Mexican actress contracted with the studio, and he would create film opportunities for her in Los Angeles to discourage her from moving back to Mexico City. Dracula was one such film. For what it’s worth, Kohner and Tovar were married in 1932 and stayed happily together until the former’s death in 1988 (Mallory 49-51).

Spanish Dracula was directed by George Melford, who had previously directed The Sheik with Rudolph Valentino in 1921. He was no stranger to Spanish remakes, either, having directed a Spanish version of Universal’s The Cat Creeps in 1930. Filming for Dracula was done at night, once the crew for the English version had wrapped up for the day. Melford was able to watch the dailies for the English version (i.e. the footage shot on that day), and he used those to guide his direction. Another fun fact: Melford didn’t actually speak Spanish, and he had to direct the cast and crew via an interpreter. When you take the language barrier into account, it’s surprising that the film ended up being so good. Many critics over the years have even called it better than the English version. And in some respects, it actually is.

In terms of technical aspects, Spanish Dracula is largely similar to the original film. Scenes are in the same order, the music and sound cues are the same, etc. The main differences are found in the camera work. While Browning keeps the camera static most of the time, Melford uses more dynamic shots. When Dracula meets Renfield, for example, we get a slow crane shot that pans up the castle stairs to show Dracula on the landing.

The main differences I want to discuss are in the script and the acting. Spanish Dracula has a slower pace than the English version: it’s about 20 minutes longer, and more focus is placed on the heroes debating how to stop Dracula. The extra length is due mostly to a few additional scenes of Van Helsing interrogating Renfield or giving an explanation to the whole group. To be honest, you don’t really notice the extended runtime. There isn’t anything in the film which feels like it shouldn’t be there. It even fixes the loose ends from the English version: we see the aftermath of Lucy getting staked, and Van Helsing’s unfinished business at the very end of the film is burying Renfield’s body as he’d promised to do earlier. If I had to guess, these were probably scenes from the English script that had been cut for time.

The most interesting differences are in the actors’ performances. Carlos Villarias was apparently the only cast member who saw the English version, and he was told to imitate Lugosi’s performance as closely as possible. Villarias’s Dracula, however, is a lot more convincingly human than Lugosi’s. It’s much easier to imagine him fooling Seward and the other humans into thinking he couldn’t be a threat. But he stumbles when it comes to making Dracula seem actually scary. While Lugosi has that icy stare that goes right through you, Villarias has “crazy eyes.”

Pablo Alvarez Rubio, who plays Renfield, brings a lot more manic energy to the role than Dwight Frye does. Spanish Renfield is literally screaming nuts. I think the best way to compare the two is to watch both versions of the “rats” monologue. Frye has a restrained and ominous tone throughout and seems to be relishing the memory of his encounter with Dracula, while Rubio nearly has a breakdown in the middle of his dialogue as though he’s realizing how effed up what he’s saying is. It’s a somewhat different take on the character, but no less valid or high-quality than Frye’s performance. They are both among the best parts in their respective versions.

There is one instance where I think the acting in the Spanish version is noticeably better than the English version, and that’s with Mina (or “Eva” as she’s called here). Helen Chandler’s performance doesn’t have much enthusiasm behind it and is pretty unmemorable overall. Her behavior and demeanor when she’s under Dracula’s control isn’t that different from how she acted before that point. Lupita Tovar’s performance as Eva is a lot more varied and interesting. Like with Renfield, you get the sense that she’s aware of what’s happening to her and that she’s afraid of accidentally harming her loved ones. Beyond that, you can see Dracula’s growing influence over her in how she becomes more relaxed when he’s present. And towards the end, when he’s controlling her almost completely, her sudden perkiness is downright unsettling. You can tell that something’s very wrong even before she tries to take a bite out of her fiance’s neck.

Spanish Dracula may not have Bela Lugosi’s iconic performance at its helm, but it makes up for that by being a slightly stronger film overall. It manages to smooth out the narrative holes and inconsistencies that were present in the English version while retaining the grim atmosphere that makes the English version so good. Villar’s Dracula is just okay, but Rubio’s Renfield is great fun to watch and Lupita Tovar creates a more lively, engaging female lead than the English version has. Right now this film is only available in certain Universal compilations and box sets, but hopefully it will get an individual release. It deserves to be recognized as a great horror film along with its counterpart.

Final Rating: 4 Stars

Dracula was a gamble that paid off for Universal. Within the first forty-eight hours of its theatrical run, it had sold 50,000 tickets, a high number back then. It ended up making a profit of $700k, becoming the largest of Universal’s 1931 releases. Critics at the time praised the film and especially Lugosi: he would play the role of Dracula only one other time after this, but his name would be synonymous with that role for the rest of his life and beyond. Universal had a new hit and a new star on their hands, and it was only February. Their big year was just beginning…

UP NEXT: Frankenstein (1931)

Works Cited & Further Reading

Mallory, Michael. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror. Universe Publishing, 2021.

Landis, John. Monsters in the Movies: 100 Years of Cinematic Nightmares. Reprint, DK Publishing, 2016.

Herzogenrath, Bernd. “Introduction.” The Films of Tod Browning, edited by Bernd Herzogenrath, Black Dog Press, 2006, pp. 10–17, archive.org/details/filmsoftodbrowni0000unse.

Lennig, Arthur. The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi. Kindle ed., The University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Bronfen, Elisabeth. “Speaking With Eyes: Tod Browning’s Dracula and Its Phantom Camera.” The Films of Tod Browning, edited by Bernd Herzogenrath, Black Dog Press, 2006, pp. 151–71, archive.org/details/filmsoftodbrowni0000unse.